If I were twenty years younger, or maybe even ten, The Serpent Called Mercy might have struck me as a breath of fresh air, a vigorous indictment of systematic economic and social disenfranchisement viewed through the lens of a friendship tested by ambition, misunderstanding, and shame, with extra gladiatorial beast-fighting combat. As it is, I admire Roanne Lau’s debut novel for its studied subversion of all the more usual tropes of a competition-focused fantasy novel, while finding that my appreciation never really rose above the intellectual.

Lythlet Tairel is a young woman from a poor background scraping out a living in a fantasy city that has an excuse for a social safety net that’s even worse than the USA’s, and worker protections that are worse still. In this unregulated and corrupt environment, she and her best friend Desil—her only friend—are in significant debt to an unscrupulous moneylender (is there any other kind?) who enforces the terms of his compounding interest with beatings. Desil used to make good money as a bare-knuckle fighter, but gave it up from religious conviction: He does not want to be violent towards another person again, and is haunted by guilt. He currently works in a teahouse. Lythlet who, after tolerating a long string of physically abusive employers, has ended up in a disastrous lack of employment, has finally turned to theft. She’s not particularly accomplished at it. In order to pay off their debt, they need much more than they’ve got. And Lythlet, at least, doesn’t want to pay off the debt only to slide back down into more debt. She’s angry. She’s ambitious. She wants the security to reach for happiness and plenty.

How fortunate for her, then, that a technically-illegal fighting ring is recruiting pairs of “conquessors” for its next series of matches. This ancient bloodsport pits pairs of humans against terrible beasts that frequently have some kind of extra special power: “sun-cursed monsters,” as they are called. There is one match a month for a year. Few stay the whole course, and few survive it: The pairs of combatants are sworn together, and neither is permitted to concede a match, or leave it, unless both agree to forfeit. Combatants who win take a percentage of the match-organised betting, but only of the bets on their victory.

For Lythlet, this seems like the answer to most of her troubles—though in her initial ignorance, she doesn’t realise how dangerous it is. Desil is more hesitant but agrees, and the games’ organiser, one Master Dothilos, agrees to let them compete. A significant proportion of The Serpent Called Mercy revolves around these combats, and on Lythlet’s relationship with Dothilos and with Desil as their growing success in the games alters both.

Lau has a solid grasp of action scenes. The individual combats are well-written, tense, and easy to follow. There are some unusual (in fact, downright subversive) choices: Lythlet, in her first fight, interacts with a plant and unlocks a special power, not used in many years and practically mythical, that allows for her and Desil to survive and win, but thereafter it is hardly touched on.

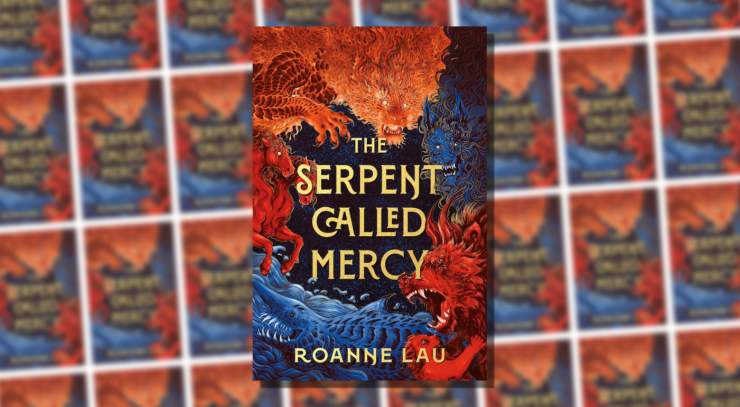

Buy the Book

The Serpent Called Mercy

In Master Dothilos, instead of either a mentor or someone who wants only to use her, she finds both. Dothilos is an ambitious man, risen from poverty to wealth, deeply enmeshed in the corruption that undergirds most aspects of the state. He comes to see in Lythlet someone whose potential reminds him of himself. He plays on her ambition to turn her into someone he can use outside the games as well as within them, while also acting in part in what he sincerely sees as her best interests. Lythlet is sufficiently ambitious to find many of his arguments convincing, but the pressure he exerts on her to comply makes her obstinate. It also gives her cause to find reasons in her conscience and what I can only term a nascent sense of class solidarity as to why he is unpersuasive. Meanwhile, she is approached by political opponents of Dothilos’s likely patron, who seek evidence of the elected head of government’s involvement with corruption: evidence that could put the brakes on said head of government’s prosecution of his opposition.

Lythlet and Desil’s success in combat strains their friendship, as Desil struggles with his relationship to violence and worries for Lythlet’s safety and survival. This strain becomes even sharper when Desil tries to force a forfeit—primarily for the sake of Lythlet’s safety—as he becomes convinced that they can fight on and win.

There are two paths before Lythlet: the path of ambition, which will break her friendship and quite possibly all her remaining morals, and the path that honours her friendship with Desil and her connections with fellow members of the city’s marginalised underclass, and leads to more poverty and possibly to her death.

The Serpent Called Mercy is filled with the economic exploitation and abuse of people in poverty. It sets itself in a city where the most powerful man is also the most corrupt, where child murderers and the procurers of children are protected because of their usefulness to the wealthy, where undocumented workers are worked to death on purpose and reporting child exploitation to the equivalent of the police results in employment blacklisting, rather than action. It is, in short, very much a book steeped in disillusionment with the current political and social moment in much of the Anglophone world, with the trappings of democracy and justice rather than its substance, and it wears its anger at injustice on its sleeve. (It also, rather effectively, subverts many of the narrative expectations for a novel structured around a set of gladiatorial combats.) Were I younger, as I said, I suspect it would resonate more for me, but its outrage at the idea that the game is rigged from the start is wasted on me. Lythlet’s eventual resolve to value mercy and connection moves me far more.

Her friendship with Desil—and her surprise when she finally learns that she’s put him on a pedestal, and that he too has struggles she doesn’t see—is well-drawn. They are different people with different needs and at times different goals, and they have to figure out whether, and if so how, to value their friendship around those differences. It’s a pleasure to read a novel where the primary relationship is platonic, though it’s clear that Lythlet, like many young people in stressful circumstances, is somewhat self-absorbed. The Serpent Called Mercy is a compelling debut, from a writer with a subversive bent towards some interesting themes. I look forward to seeing where Lau goes next.

The Serpent Called Mercy is published by DAW.